American Judiciary, Part 2: An Independent Federal Judiciary

One of the first pieces of legislation crafted in the first Congress was the Judiciary Act of 1789, signed into law by President George Washington on September 24. This act established that “The supreme court of the United States shall consist of a chief justice and five associate justices” and that it would meet in two sessions each year in the nation’s capital.” President Washington nominated six Supreme Court justices, including John Jay as the first chief justice, but his appointments were based as much on political orientation as on judicial experience. However, in the election of 1800, Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party swept John Adams and the Federalists from power, capturing the presidency and both houses of Congress.

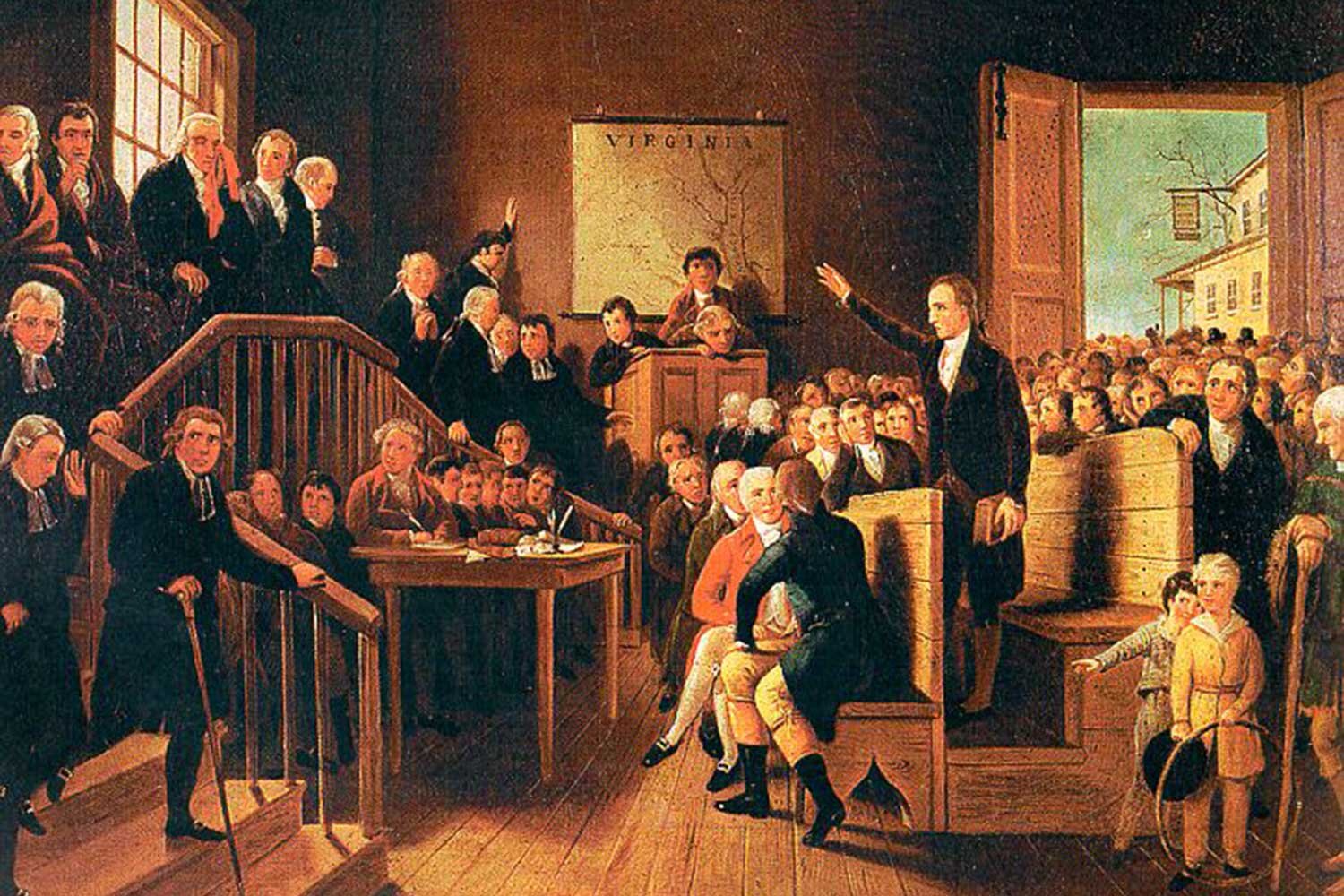

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, discusses how the federalists took control of the national judiciary, and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of Library of Congress, National Archives, National Portrait Gallery - Smithsonian Institution, New York Public Library, Encyclopedia Virginia, National Gallery of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wikimedia.

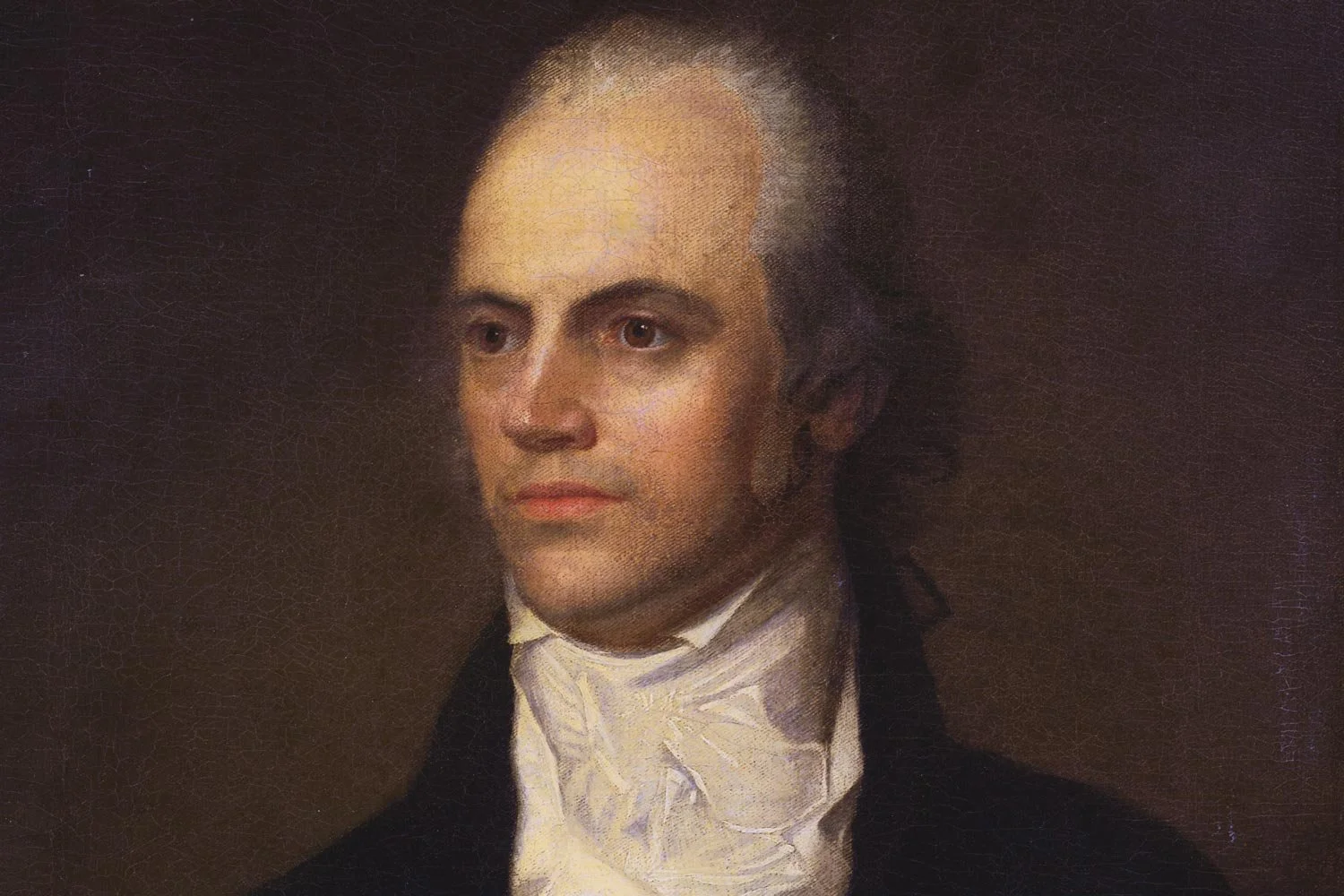

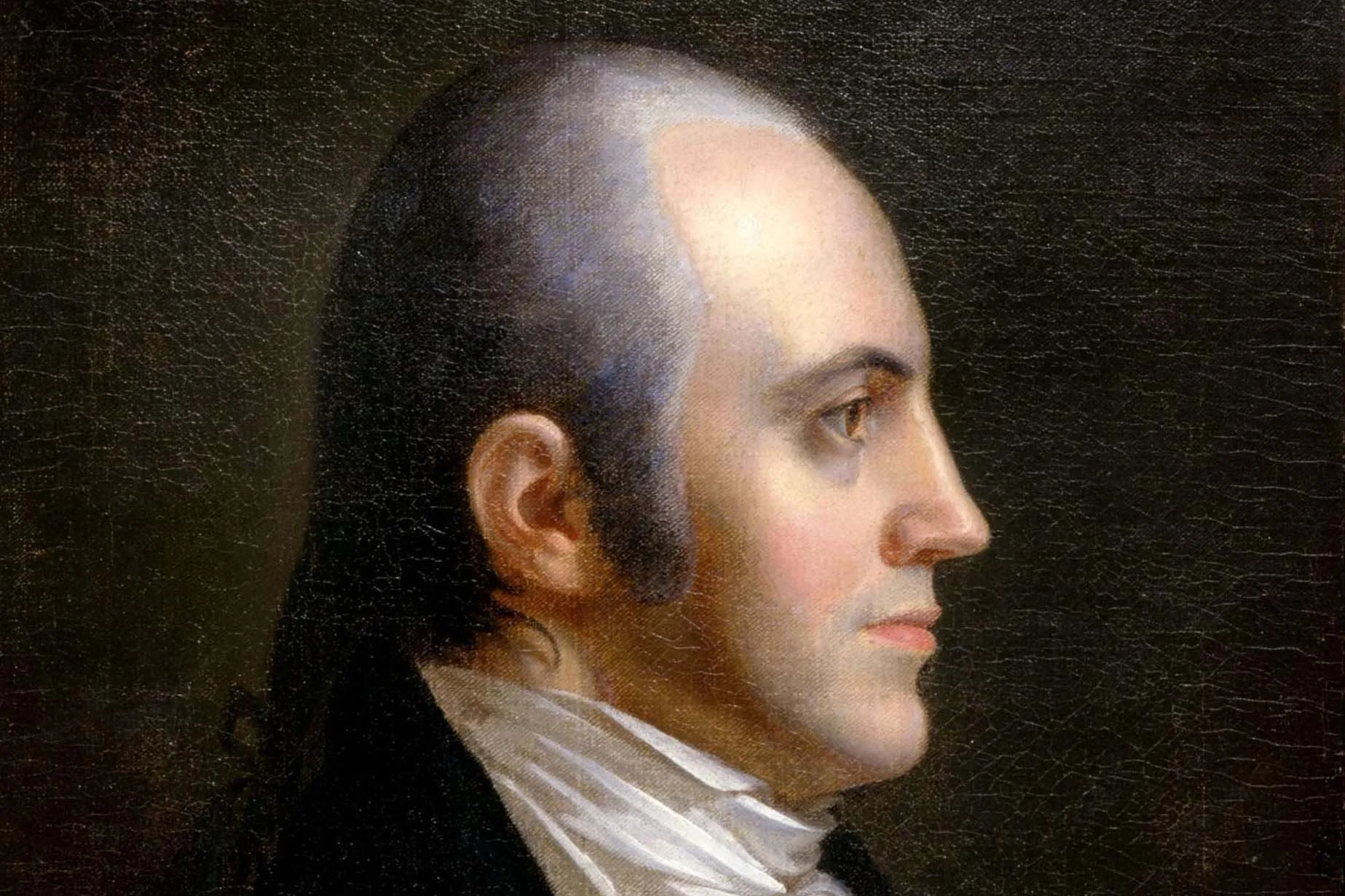

Aaron Burr's grand scheme to create his own country, possibly in Mexico or from United States territory, began to collapse late in 1806, practically before it ever got started. This empire in the sky built largely in Burr’s fertile mind was swiftly coming to an end.

Aaron Burr was one of the most talented of our founding fathers, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Continental Army, an accomplished attorney in New York, a United States Senator, and the third Vice President. But Burr also happens to be the only sitting or former President or Vice President ever tried for treason in arguably the most important criminal trial in American history.

There has been only one instance in our nation’s history of a United States Supreme Court Justice being impeached, and that occurred in 1804 during a significant political tussle over the independence and power of the judiciary. The justice in question was Samuel Chase and his alleged crimes seem trivial in retrospect, but Chase was simply a pawn in an ongoing battle of wills between two American icons, President Thomas Jefferson and Chief Justice John Marshall that took place in the early 1800s. And the decision reached in his case would have a profound impact on the future of the country.

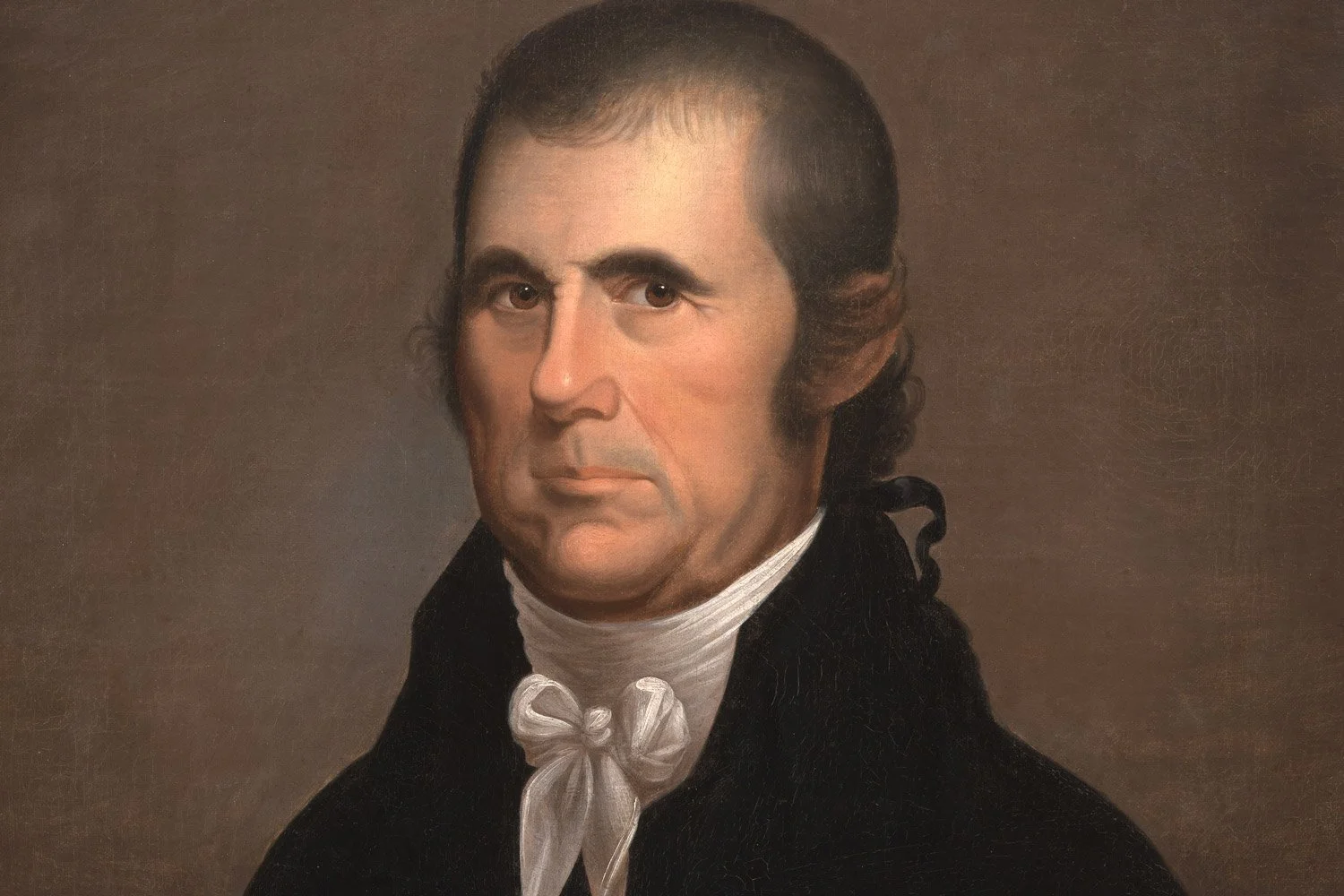

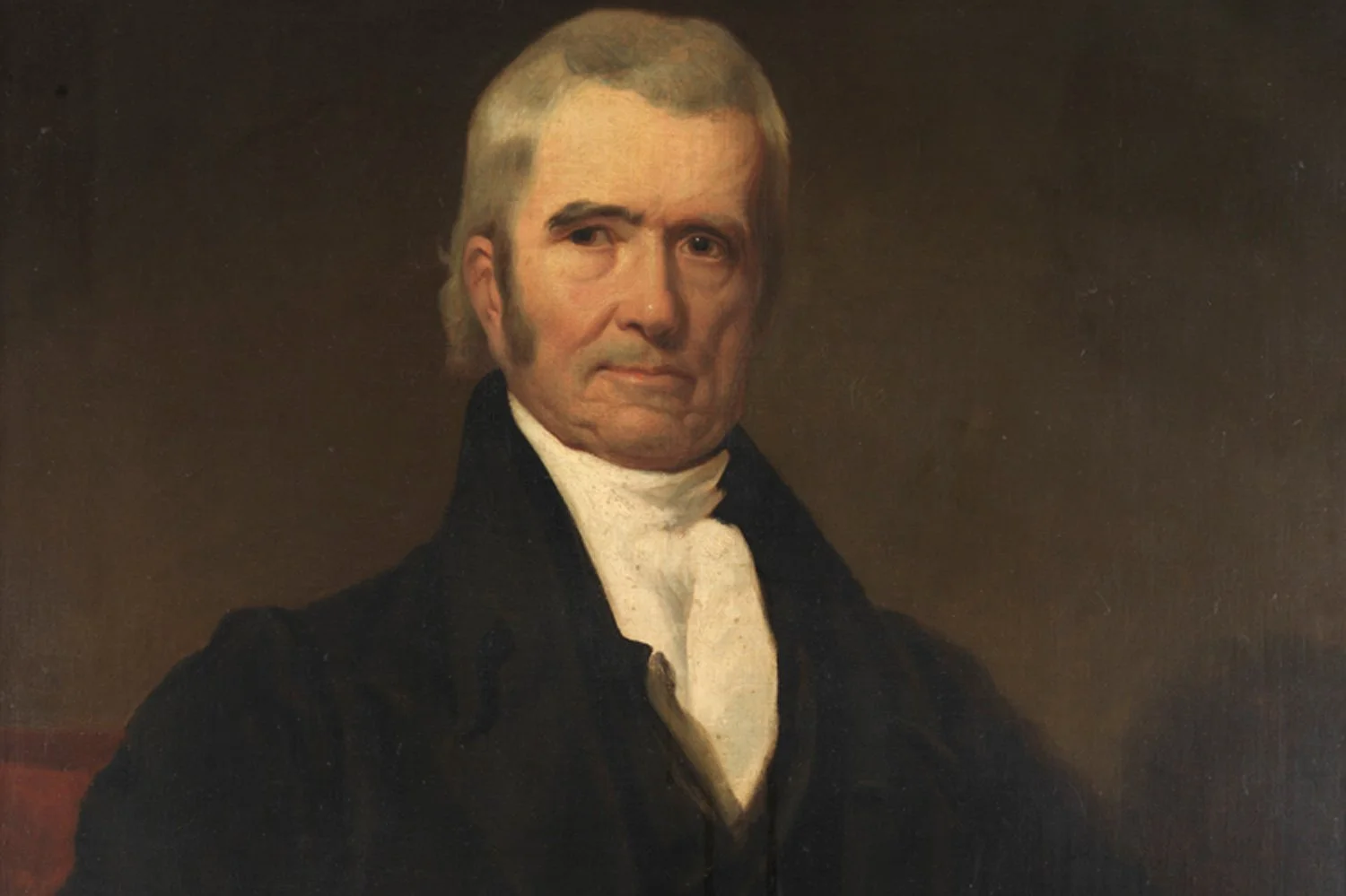

Marbury v Madison is the most consequential legal decision in our nation’s history because it established the concept of judicial review in the United States. This principal grants to the judiciary the responsibility to review laws for their constitutionality and gives it the power to void legislation it finds repugnant to the Constitution. That decision was rendered by John Marshall, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1803, but the road to that decision extends further back.

John Marshall's active service in the Continental Army ended in December 1779, although he did not officially retire from the military until February 1781. Marshall went home to Virginia to await his next command, anxious to get back into the fight, but that call never came as the war in the north wound down.

In early December 1775, Major Thomas Marshall and his son, Lieutenant John Marshall, and the rest of the Culpepper Minutemen were ordered to join Colonel William Woodford at Great Bridge, a small village nine miles south of Norfolk. Here, in the first fight of the American Revolution in Virginia, the young Lieutenant from the frontier would get his initial taste of battle.

John Marshall is perhaps the most impactful and influential man in American history who was never president. Almost single handedly, John Marshall created our national judiciary and established it as a branch of government co-equal to the legislative and executive branches.

After the Federalists were voted out of office in the fall of 1800 by Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party, the need for reform to the judicial system, the last stronghold of Federalist authority, became the most pressing concern of the outgoing Adams administration.

One of the foundational governing principles of the Constitution created at the Philadelphia Convention in the summer of 1787 was a separation of powers between the national legislative, executive, and judicial branches. But while significant operating concepts and responsibilities were set forth for Congress and the Executive in the Constitution, the delegates barely addressed the specific structure of the Judicial branch.

The court system in Colonial America, not surprisingly, mirrored that of Great Britain and became one of the great sources of discontent as American colonists moved towards independence. The main issue was over who would control or have the greatest influence on the judiciary.

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.